The exhibition Helmut Newton. Brands brings together over 200 photographs, including many unknown motifs from Newton’s collaborations with internationally renowned brands such as Swarovski, Saint Laurent, Wolford, Blumarine, Redwall, and Lavazza.

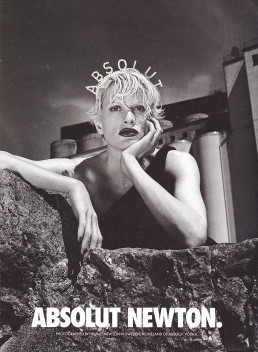

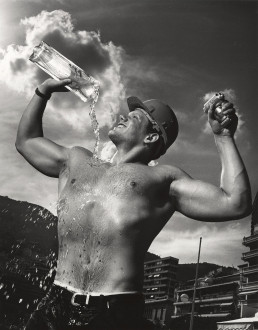

When it came to composition and style, the photographer did not differentiate between magazine editorials and direct brand commissions, which were often arranged through advertising agencies. Newton referred to himself ironically as A Gun for Hire – a term that also served as the title of the 2005 posthumous exhibition of his commercial photography, shown first at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco and then at the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin. Included in the exhibition at that time was Newton’s extravagant, award-winning black-and-white ad campaign for Villeroy & Boch from 1985. Newton showed the brand’s sinks and toilet bowls being delivered to a prestigious villa – carried by young women – with constellations of figures more reminiscent of Raymond Chandler’s detective novels than everyday life. His aesthetic rendering of both luxurious and everyday products and the remarkable shift in conventional contexts of use are captivating. Only a few photographs from the earlier exhibition on Newton’s commercial photography will be on view in Helmut Newton. Brands – such as the magnificent black-and-white series for Absolut Vodka with Kristen McMenamy, produced in Sweden in 2000.

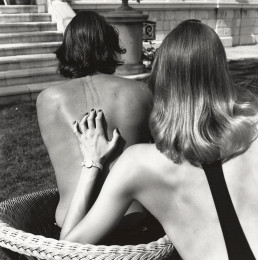

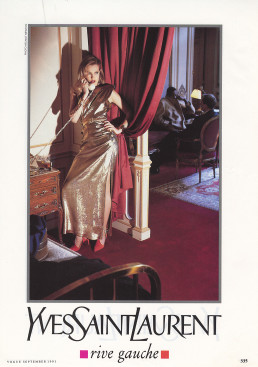

Helmut Newton. Brands picks up where A Gun for Hire left off, showcasing photographs Newton shot mainly in the 1980s and ’90s for high-paying advertising agencies and corporate clients, mostly in and around Monaco. In the three front exhibition rooms, we encounter fashion images produced for the luxury industry, such as Newton’s interpretations of Yves Saint Laurent’s latest fashion designs, from haute couture to prêt-à-porter. Newton’s productions from season to season are as diverse and individual as the women’s clothing he depicted. The visual compositions sometimes transcend reality, transporting us to distant emotional and exotic spheres.

The other two rooms show Newton’s commissioned works for Wolford, which were published in 1993 and 1994 as calendars for exclusive customers. Newton’s photographs were used on everything from pantyhose packaging to XXL formats on billboards, public buses, and building facades. Such shifts in size and context, of course, radically alter the effect of the photographs, even while the subjects remain the same: when presented in the public space, the women modeling pantyhose and tight-fitting bodysuits transform into giants. Newton shot the Wolford campaign in both black-and-white and color with several models in Monaco, mainly near the sea. His images of designer creations for the American luxury department store chain Neiman Marcus are also on display in the first three exhibition rooms. They include examples from Newton’s many years of close collaboration with Anna Molinari and her label Blumarine, featuring models such as Monica Bellucci, Carla Bruni, and Carré Otis, realized in Nice and Monaco in 1993 and 1994.

What all these advertising campaigns have in common: Newton only integrated a few images from his commercial photography series into his exhibitions and books during his lifetime. Now for the first time, Helmut Newton. Brands offers the possibility to experience these photo series in their entirety in a single exhibition.

Over the years, Newton became a veritable marketing expert for a wide variety of products. Advertising photographs are a natural part of our product- and brand-oriented consumer world; they are omnipresent and a vital component of any corporate strategy. To be effective, the images must be surprising and, above all, seductive, convincing us to purchase the visualized product. The photographer repeatedly fulfilled these requirements with great success, blending timeless elegance and provocative exaggeration. Early examples of commercial photography from the Weimar Republic, for example, by El Lissitzky, Jan Tschichold, Sasha Stone, or Albert Renger-Patzsch, are also icons of the Neues Sehen (New Vision) movement, which treated photography as a medium of artistic expression, and are therefore considered fine art. This contextual shift also applies to some of Newton’s timeless advertising campaigns, even though he always insisted on being called a photographer rather than an artist – a self-description that experts have contested over the years.

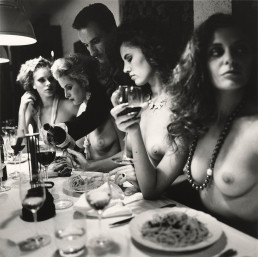

On view in the main room of the Helmut Newton Foundation are further little-known motifs: photographs Newton produced for the tobacco companies Philip Morris and Dannemann, for the Turin-based coffee roaster Lavazza, the Italian vintner Ca’ del Bosco, and the Austrian DIY store Bauwelt. Likewise shot in the 1980s and ’90s, each motif is highly individual, oriented to the brand and its offerings while reflecting Newton’s signature style. These images were also initially distributed in the form of exclusive, sometimes limited and numbered wall calendars, quickly becoming prized collector’s items traded at high prices. A selection of these calendars has been displayed in the permanent exhibition Helmut Newton’s Private Property for years, presented in box frames. However, only one motif is shown at a time and is changed periodically. Interestingly, the calendars were produced in a variety of formats, with spiral binding or tear-off pages and occasionally with the same motif over two months. Otherwise, they followed a classic format with twelve alternating motifs from January to December. Yet other advertisers produced calendars featuring preexisting Newton motifs that were not explicitly advertising images. The photographer seemed to have been quite open to this means of distributing his images, although each use and its duration were contractually regulated between the respective advertising agency and Newton’s agent.

In the rear exhibition rooms, we can discover further collaborations, such as with the fashion jewelry manufacturer Swarovski, Volkswagen, the luxury emporium Asprey, and Chanel. In the mid-1970s, Newton even directed two television commercials for the famous perfume Chanel No 5, starring Catherine Deneuve. Display cases show various Polaroids, analogue contact sheets from advertising shoots, lookbooks from fashion clients, and magazine ads, pointing to the diverse uses of Newton’s advertising photography. The juxtaposition of the individual photographs hanging on the exhibition walls and the same motif in its advertising context is quite illuminating. We can see both the enlarged print and the image in its original format in the magazine or brochure, accompanied by typography or other graphic design elements. Newton’s photographs were generally not superimposed with text but only supplemented by the client’s logo – the image’s message was meaningful enough.

Newton started collaborating with fashion brands outside of magazine editorials early on. For example, from 1962 to 1970, he worked with Nino-Moden in Nordhorn, West Germany’s largest textile company at the time, and shot the catalogue for London-based Biba in 1968. That same year, he accepted a commission from the French car manufacturer Citroën for a brochure advertising the legendary DS series. This and more can be found in the display cases on view in the exhibition. Until shortly before his death, Newton continued to produce editorials for different magazines but also advertising campaigns, such as for Alberta Ferretti in Monte Carlo in 2003. That same year, he produced an unpublished black-and-white campaign for tablets against erectile dysfunction called Levitra®, a Viagra-like medication by the pharmaceutical company Bayer. However, the campaign was stopped before publication under threat of a lawsuit. To the very end, Newton remained curious about the almost infinite possibilities of visualizing a wide variety of products. In doing so, he flaunted the boundaries of both morality and genre: nudes became advertising motifs for the Spanish brandy Osborne Veterano, for the Volkswagen Beetle, and for Montblanc’s Meisterstück fountain pen. A seemingly lifeless woman lying on the floor in a garage advertised a Prada bag strategically placed in the picture’s foreground – a particularly striking example of “radical chic.” A self-portrait of Helmut Newton, with a camera on the table and his wife June at his side, presents the luxury wristwatch manufacturer Rolex. In all instances, everyone is highly convincing in their role.

For decades, Newton staged everyday and luxury products, becoming a link between producers and consumers through his photographs and their publication. Advertising is also about communication, conveyed through the product’s image, and Newton always added an unexpected plot. At the same time, his visual narratives were universally understandable, so magazine publishers could easily include them in their different country editions, whether as editorial or advertising. These successful productions were often prepared with the help of Polaroid images. Newton used them to ascertain the effect of his visual compositions and discuss them with the designers, advertising agents, or clients during the shoot. Hundreds of examples in the foundation’s archive and a small selection in the exhibition display cases bear witness to this.

These famous and lesser-known series are all featured for the first time in this retrospective of Helmut Newton’s advertising photography. The often underestimated yet influential area of applied photography deals with the visualization of products for commercial purposes. In Newton’s case, these products included women’s pantyhose, evening gowns, ground coffee, television sets, saw blades, silverware, red wine, cars, wristwatches, costume jewelry, cigars, and potency pills. Sometimes Newton made the objects the center of attention, placing them literally on a pedestal, while in other images, they are relegated to the sidelines. An advertising image that does not explicitly show the advertised product but only conveys its purported effect, for instance, in the case of perfume, is referred to as “mood photography.” It creates a specific atmosphere intended to spark an emotional connection between the product and the reader of the magazine where the advertising image is printed. Newton mastered the entire spectrum of stylistic and thematic possibilities like no other. Not only did he influence the taste of the times; his images shaped the zeitgeist for decades, sometimes redefining it entirely. Newton’s usual starting point was a female model performing a daring act and breaking with the prevailing norms. His commercial photography thus transformed fictitious narratives into possible realities. Entrusted with a virtual carte blanche by many of his clients, he pushed the boundaries of what was morally permissible or blurred the lines between truth and lies. In advertising, he was not restricted by narrow editorial policies, as with American Vogue, for example, but was able to work much more freely and radically in his compositions.

One of the Helmut Newton Foundation’s central tasks is researching visual motifs in its in-house archive by reviewing older publications, contact sheets with Newton’s handwritten markings, and work prints and bringing them into new contexts through thematic exhibitions. Commercial advertising photography represents one of the most important aspects of Newton’s work. The presentation of numerous previously unknown photographs makes the current exhibition Helmut Newton. Brands essential for a comprehensive and systematic analysis of his oeuvre.

Matthias Harder