The summer exhibition at the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin is again divided into three parts. Highlighting the works of Alice Springs, Helmut Newton, and Mart Engelen, it not only unites three photographers, but also three different photographic approaches.

Under the pseudonym Alice Springs, June Newton also worked as a photographer, with a particular focus on portraiture. This is her second retrospective, organized in 2015 by the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, now also be shown in Berlin, showcasing more than 100 portraits she has made of fellow photographers, as well as other prominent figures, both in black & white and in color. They are complemented by an expansive series of street photographs Alice Springs shot along Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles, where she documented the Californian punk and hip-hop scene in the 1980s.

Helmut Newton did not only work exclusively for fashion magazines and designers. He also nurtured an interest in offbeat subjects, paparazzi pictures, police photography, and crime stories, in short: yellow journalism. The exhibition Yellow Press was compiled and first presented by the photographer himself in 2002 at his former gallery in Zurich. It includes several photo series that were never published in Newton’s books during his lifetime.

Once again, Helmut Newton’s wish to invite a photographer to exhibit in “June’s Room” will be posthumously fulfilled. Amsterdam-based photographer Mart Engelen, who also publishes an exclusive photography magazine, will show more than 20 black & white portraits from the international contemporary cultural scene, inspired by French film noir.

Selected Works

Springs – Newton – Engelen

Matthias Harder

The summer exhibition at the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin is again divided into three parts. Highlighting the works of Alice Springs, Helmut Newton, and Mart Engelen, it not only unites three photographers, but also three different photographic approaches.

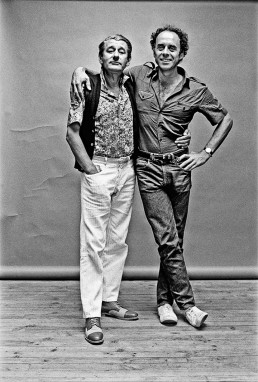

Under the pseudonym Alice Springs, June Newton, widow of the legendary photographer of fashion and nudes, has worked since 1970 as a photographer, primarily in the field of portraiture. Alice Springs and Helmut Newton often exhibited their works together, especially their joint project Us and Them. In 2010, the first Alice Springs retrospective was hosted at the Helmut Newton Foundation, where it filled the entire exhibition space. Now in the summer of 2016, a second, somewhat smaller retrospective, organized in 2015 by the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, will be shown in Berlin and again accompanied by a book by TASCHEN publishers. In her many portraits of fellow photographers, such as Richard Avedon, Brassaï, Ralph Gibson, and of course Helmut Newton, and of celebrities including Nicole Kidman, Audrey Hepburn, Christopher Lambert, and Claude Chabrol, Alice Springs succeeds in capturing both their outer appearance and their aura. The wordless dialogue that leads to such extraordinary portraits seems to stem from a kind of spiritual kinship that she shares with her subjects.

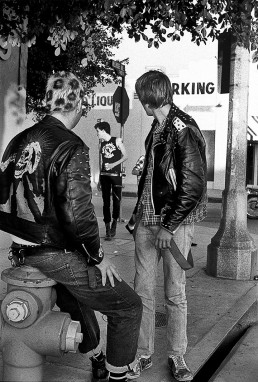

These powerful images in both black & white and color are complemented by an extensive street photography series that Alice Springs shot along Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles, where she attentively documented California’s punk and hip-hop scenes during the 1980s. Anarchic youth culture, marked by radical hairstyles and shrill body piercings, rejected the notion of capitalist society. Only a few years later, this music- and fashion-based protest movement in California subsided; what remains is this artistic inventory of the spirit of the times.

The photographic career of June Newton a.k.a. Alice Springs was sparked when Helmut Newton became bed-ridden with the flu. In Paris 1970, June Newton had her husband instruct her on how to handle the camera and light meter and took his place in photographing a promotional image for the French cigarette brand Gitanes. Her portrait of a model smoking signaled the start of a new vocation for the trained theater actress, who had few work prospects in France, especially due to the language barrier. José Alvarez, who ran an advertising agency in Paris, subsequently commissioned her to produce commercial photographs for pharmaceutical products. From the mid-1970s onwards, Alice Springs focused increasingly on portraiture. In 1983 Alvarez, then as head of the publishing house Éditions du Regard, released her first volume of portraits. Radiating with empathy for their human subjects, some of these images are now iconic. Their noticeable blend of rapport and curiosity continues to make the work of Alice Springs so interesting today.

Although most of her subjects count among the cultural jet set, in her approach Alice Springs does not differentiate among the social classes. Alongside prominent actors, directors, and writers, her oeuvre includes equally compelling images of the Hell’s Angels and anonymous L.A. punks. She usually closes in on people’s faces, or frames them in a tight bust or waist shot. Looking straight at the camera, her subjects seem curious and sincere. There are few studio portraits; most have been taken with natural lighting, in public places or at the protagonist’s home. In these subtle portraits we encounter poses that suggest vanity or natural self-confidence, as well as shy glances. From magazine commissions to her independent initiatives, Alice Springs’s portraits are visual commentaries that convey a sense of intensity and intimacy without compromising her subjects. She allows each unique personality to shine through, resisting cliché to offer us new and unconventional views. Her keen ability to both reveal and penetrate a person’s façade might be traced to her solid foundation in acting; this applies particularly to her double portraits, where the subjects’ interaction appears almost staged.

Among these are also portraits of her husband, usually in tandem with well-known colleagues, or captured behind-the-scenes during a photo shoot. Together with intimate self-portraits, they round out the comprehensive retrospective. This collection of mostly private images can also be viewed as a companion to the joint exhibition Us and Them, which was shown in 2004 and again in 2014 at the Helmut Newton Foundation. Until now, most of these photographs have not been on public display. With their presentation, the interconnected life and work of the two photographers is brought full circle in this Berlin exhibition.

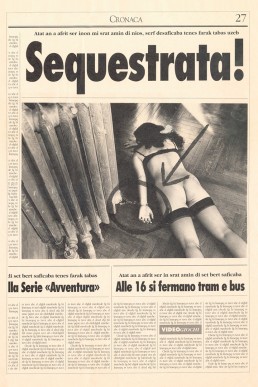

Helmut Newton worked not only for fashion magazines and fashion designers, but also nurtured an interest in offbeat subjects, paparazzi pictures, police photography, and crime stories. In short, for “yellow journalism,” a mix of tabloid press and articles from the “Miscellaneous” section of daily newspapers. The exhibition Yellow Press, which was compiled and first presented by the photographer himself in 2002 at his former gallery in Zürich, de Pury & Luxembourg, is an eclectic mix culled from works Newton realized between 1973 and 2002. It includes several photo series that were never published in Newton’s books, such as his self-titled photo essay “Self-Appropriation,” a nude editorial for Playboy magazine on the Lolita theme, and a documentation of court proceedings in Monaco that he shot for the magazine Paris Match.

For Yellow Press, Newton re-photographed his own published images, and the resulting facsimile sometimes includes the entire magazine page with headlines and other articles or dummy text surrounding his picture – and transferred them in new huge prints. Among these is a series in search of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, which Newton shot in the mid-1970s for Playboy magazine in Florida. Twenty-two-year old model Kristine DeBell slipped into the role of the child-woman for Newton, posing nude or lightly clothed in motels and in an American cruiser car. The photographs were originally published in Playboy in August 1976. Around this time, DeBell gained international recognition for her role in the notorious pornographic version of Lewis Carrolls’s Alice in Wonderland, directed by Bud Townsend.

Newton’s 2002 photo documentation of the trial against Ted Maher, the former nurse of Lebanese-Brazilian banker Edmond Safra, would not necessarily be associated with his usual work. Newton was commissioned by the illustrated weekly magazine Paris Match to cover the court proceedings in Monte Carlo against Maher, who was held responsible for the death of his patient in December 1999. Newton approached the hearings in the style of a court reporter: quickly and using color film, sometimes shooting off-center or standing within a crowd of other photojournalists.

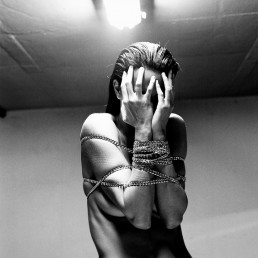

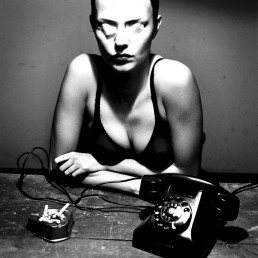

At the heart of the enigmatic, 18-part black & white series The Woman on Level 4 is a young woman that Newton photographed in a small, windowless room. She is pictured nude, or wearing a semi-transparent bra with her eyes covered, then in black stiletto heels holding a semi-automatic gun, or clad in a dark leather jacket with an old-fashioned telephone. Seen together, the images offer a kind of a visual detective story, yet without beginning or end. The woman with covered eyes, who no longer wants – or is able to – see is paradigmatic for the closed, empty chamber, an eerie, claustrophobic stage on which the protagonist seems to revolve around herself. The final images depict the model holding an article torn from an English-language newspaper, addressing a mysterious murder case from 1923. But Newton actually shot the images in the year 2000 in the garage of his apartment building in Monaco. In the series, he forgoes chronological narration, instead playing with a cinematic chain of association that cuts hard to each new scene.

Newton’s short promotional film for the Italian zipper manufacturer Lanfranchi from the 1980s can also be seen, along with Polaroid images that Newton shot of this film from a TV screen. His ironic paraphrasing of a sadomasochistic fantasy is an unconventional yet compelling element of the Yellow Press exhibition. The Polaroids can be understood as a form of self-appropriation. Once again, Newton skillfully stages a dramatic situation using a model and a few props, steering our voyeuristic gaze to views of despair and masquerade, intimacy, and narcissism. Power, Eros, and the thrill of danger are frequent elements in Newton’s visual universe. He cleverly combines tabloid and tragedy to create both spectacle and social commentary, about whose outcome Newton, as director, keeps us wondering.

Many of the photographs and artistic approaches that we encounter in this exhibition enrich and expand the general image we have of Newton and his work. Because they comprise the last series that was selected by the photographer himself, Yellow Press is tantamount to a kind of legacy. In the interplay between art and commerce, Helmut Newton has always managed to surprise and provoke. In his transdisciplinary work and his work for the glossies alike, he proves himself to be an equally intelligent and sophisticated storyteller.

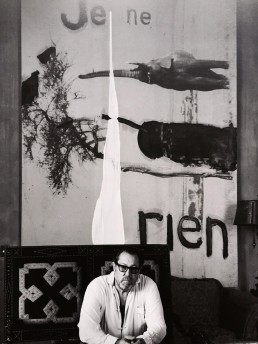

Once again, Helmut Newton’s wish to invite a photographer to exhibit in “June’s Room” will be posthumously fulfilled. For the first time in Berlin, Amsterdam-based photographer Mart Engelen will present his black & white portraits of the contemporary cultural scene – inspired in part by French film noir and including the likes of writer Michel Houellebecq, visual artists Gilbert & George, and musicians such as Pete Doherty.

Initially studying law at the University of Utrecht, during his early twenties Mart Engelen gave this up to pursue photography instead. Ten years later, he began to work professionally as a freelance photographer, with commissions from major companies and magazines such as Esquire and Vanity Fair. He lived in Los Angeles in the early 1990s, and later in the decade moved to New York City, where he decided to concentrate on black & white portraiture. Engelen has released three books of his own photography, and since 2009 has also published the exclusive photography magazine #59. That he shows many of his own pictures in each issue establishes an interesting link to Helmut Newton, who from 1987 to 1995 published the large-format magazine Helmut Newton’s lllustrated.

Mart Engelen has often photographed the beautiful and rich in their own apartments or studios, or at events such as the Venice film festival. Most of his photographic situations are quite different from official portrait sittings, during which a photographer, on commission by a magazine, might work with a model for hours, supported by make-up artists and lighting assistants. During such sessions, no matter how long or short they are, the photographer usually follows a predetermined plan to achieve the end result, sometimes also using an assortment of accessories. Mart Engelen’s work process, on the other hand, similar to that of Alice Springs, is usually much faster and spontaneous, although this might not be immediately apparent. Many of his subjects look open into the camera, whose eye is neither revealing nor idealizing – another parallel to Alice Springs.

The intensity of expression conveyed in these portraits of diverse personalities often reaches beyond their public role. Occasionally we encounter a direct confrontation between the subject and the photographer: portrait photography involves an intuitive and intellectual showdown, a kind of give and take that is at its best and most intense when a look into the eyes reveals the soul – which, in turn, the subject might parry with a deft protective stance. In such cases, good portraits can be both informative and insightful for the viewer. Mart Engelen’s development in this direction is exemplified by his portraits of Pete Doherty and William Dafoe, in which both subjects are allowed enough space for discreet self-representation. And while his compositions might be described as being traditional or classic, there is something special that stands out in Engelen’s visual depiction of his subjects, something that the experienced viewer can feel, but not always capture in words. Perhaps it is this inimitable combination of confidence and vulnerability that we come to fathom in his work.