Polaroid technology revolutionized photography. Those who have used a Polaroid camera can hardly forget the unique odor of its developing emulsion and the thrill of the instant image. With the Polaroid, every image is one of a kind. This also applies to the later large-format “Polacolor prints”, whose developing process left behind characteristic borders.

Polaroids have thus been frequently used for preliminary studies as well as a standalone medium. This was already the case early on, following the creation and presentation of the instant photograph at the Optical Society of America in 1947 by its inventor, Edwin Land – and especially after he presented in 1972 the legendary SX-70 System, a collapsible, simple and affordable camera. In nearly all photographic areas – from landscape, portrait, fashion and nudes – this unique imaging process has found enthusiastic devotees all over the world.

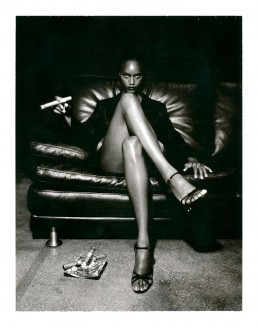

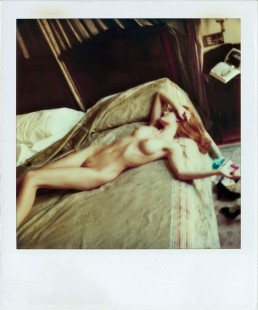

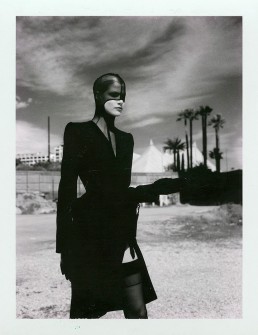

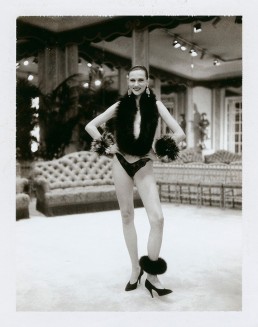

Helmut Newton used the technology intensively starting in the 1970s, especially for his fashion photo shoots. As he once described in an interview, this satisfied his impatient urge to want to know immediately how a certain situation would look as a photograph. In this context, the Polaroid acted as an idea sketch in addition to testing the actual lighting situation and image composition. In 1992 Newton published Pola Woman, an unconventional book consisting only of his Polaroids. According to the photographer, the publication lay particularly close to his heart, although it was discussed amidst great controversy. In response to the accusation that the images in the book were not perfect enough, he countered: “But that was exactly what was exciting – the spontaneity, the speed.”

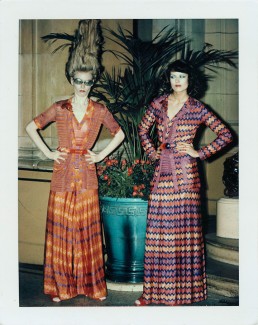

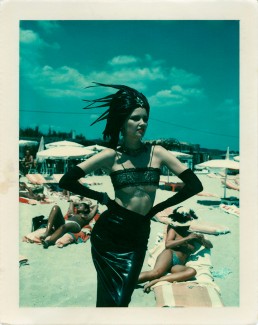

Newton’s additional notes, written on the edges of the Polaroids, are fascinating as well as revealing with regard to the model, client or location and date. The comments, the haziness of the images and the signs of use are naturally also to be found on the enlargements of the Polaroids included in the exhibition; they testify to a pragmatic and authentic approach to the original work materials, which have now posses an own inherent value. Especially interesting for today’s viewer is the unique Polaroid aesthetic that unexpectedly alters the colors and contrast of the photographed subject.

It is the first time ever, that over 300 works based on the original Polaroids offered a comprehensive overview of this aspect of Newton’s oeuvre. The exhibition is thus a look into the sketchbook of one of the most influential photographer of the 20th century. Many of the iconic photographs that have already been presented in the exhibition space of the Helmut Newton Foundation could be discovered in the Helmut Newton: Polaroids exhibition in the process of their creation.

Selected Works

Polaroid as an idea sketch

Matthias Harder

For the first time ever, over 300 works based on the original Polaroids offer a comprehensive overview of this aspect of Newton’s oeuvre. Looking at the Polaroids created at the start of his research for a fashion photograph and which manifest a remarkable sense of visual fantasy, we can study Newton’s underlying photographic concepts that were fully articulated in the photographer’s final image. The exhibition is thus a look into the sketchbook of one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. Many of the iconic photographs that have already been presented in the exhibition space of the Helmut Newton Foundation can be discovered in the current exhibition in the process of their creation.

Polaroid technology revolutionized photography. Those who have used a Polaroid camera can hardly forget the unique odor of its developing emulsion and the thrill of the instant image. It enabled professionals and hobbyists alike to hold a finished image in their hands immediately after taking a picture. The developing process was self-contained, although some camera versions required wiping a fixing agent with a sponge across the photograph’s surface. The Polaroid can thus be considered – not in a technological sense, but with regard to its rapid accessibility – a precursor to today’s digital photography, which is also valued because of the ability to check the image composition directly on the camera display. Polaroid images have also held particular appeal for art photographers due to their materiality and the possibility to reuse the image experimentally. The company’s own Artist Support Program was a further incentive for such use.

With the Polaroid, every image is one of a kind. This also applies to the later large-format Polacolor-Prints, whose developing process left behind characteristic borders. Polaroids have thus been frequently used for preliminary studies as well as a standalone medium. This was already the case early on, following the creation and presentation of the instant photograph at the Optical Society of America in 1947 by its inventor, Edwin Land – and especially after he presented in 1972 the legendary SX-70 System, a collapsible, simple and affordable camera. The small-format Polaroid cameras had already achieved marketability in 1954; but a half-century later, the long-successful process was defunct, and the world-famous American company declared bankruptcy. Nevertheless, the special cameras and films, which have gained cult status as niche products, are produced and sold in limited amounts by a small Austrian company calling itself “The Impossible Project”. The technology of instant photography remains so popular that applications have been developed for smartphones that intriguingly simulate the process.

In nearly all photographic areas – from landscape and genre, portrait and self-portrait, fashion and nudes – this unique imaging process has found enthusiastic devotees all over the world. The list of some 2,000 photographers whose works are represented in the Polaroid Photo Collection reads like a Who’s Who of modern photographic history. One finds such names as Ansel Adams, David Hockney, Philippe Halsman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Beard, Harry Callahan and Andy Warhol, the latter of whom is known for his use of Polaroids as a template for his silkscreen portraits.

Helmut Newton is of course also represented in the collection – he used the technology intensively starting in the 1970s, especially for his fashion photo shoots. As he once described in an interview, this satisfied his impatient urge to want to know immediately how a certain situation would look as a photograph. In this context, the Polaroid acted as an idea sketch in addition to testing the actual lighting situation and image composition. Newton seldom needed many test images; it was only for his Naked and Dressed series he shot starting in 1981 for the Italian and French Vogue that he used Polaroid film “by the crate”, conceded the photographer.

Since the opening of the permanent exhibition Helmut Newton’s Private Property in November, 2004, Newton’s Polaroid cameras rest among the other cameras he regularly used in a display case on the ground floor of the Museum – and form a referential context for the current exhibition. In addition to the Polaroids that Newton used as a kind of photographic sketch, he made careful mention of his ideas in his notebooks, which are also on permanent display as part of Helmut Newton’s Private Property at the Museum.

In 1992 Helmut Newton published Pola Woman, an unconventional book consisting only of his Polaroids. According to the photographer, the publication lay particularly close to his heart, although it was discussed amidst great controversy. In response to the accusation that the images in the book were not perfect enough, he countered: “But that was exactly what was exciting – the spontaneity, the speed.” In fact, the visual studies were not originally intended for publication, since Helmut Newton considered the images final only once realized on “real” film. Time and again since then, however, his Polaroids have been published in magazines, and many of his signed ones have appeared on the art market for high sums.

His additional notes, scribbled on the edges of the Polaroids, are fascinating as well as revealing with regard to the model, client or location and date. The handwritten comments, the haziness of the images and the signs of use are naturally also to be found on the enlargements of the Polaroids included in the exhibition; they testify to a pragmatic approach to the original work materials, which have now possess an own inherent value. Especially interesting for today’s viewer is the unique Polaroid aesthetic that unexpectedly alters the colors and contrast of the photographed subject.