After the great success of the exhibition A Gun for Hire at the Helmut Newton Foundation in 2005 with Newton’s fashion photos from the last 20 years the show Helmut Newton: Fired focused on his editorial work for fashion magazines of the 1960s and 1970s like Elle, Queen, Nova or Marie Claire.

“Fired from French Vogue: In 1964 I was commissioned by Queen magazine to photograph the revolutionary collection by Courrèges. The fashion editor, Claire Rendlesham, decided on a journalistic scoop showing only my Courrèges photos and excluding all other fashion houses from her Paris report. When Queen landed on the desk of Françoise de Langlade (then associate editor-in-chief of French Vogue) she hit the roof. I was called into her office, we had a tremendous row, she accused me of treachery and disloyalty and wanted to know why I had not told her about this scoop. I pointed out to her that I had no exclusive contract with Vogue, and it was of course understood that I would never divulge any ideas developed by French Vogue to Queen or vice versa. So I was kicked out of the hallowed halls of Vogue only to return in 1969 when Francine Crescent was appointed editor-in-chief. During Francine’s regime, I did what I considered my best fashion work. I was to be a regular contributor until 1982.” – Helmut Newton, from: Pages from the Glossies, Zurich: Scalo, 1998

The news of Helmut’s banishment from French Vogue soon reached Claude Brouet, the editor-in-chief of Elle magazine, who offered him work on the magazine. Helmut continued working for English and German magazines. He was able to adapt his style to the policy of the many magazines he worked for.

June Newton, Monte Carlo 2008

Selected Works

“So I was kicked out of the hallowed halls of Vogue...”

Matthias Harder

Following the great success of the exhibition A Gun for Hire at the Helmut Newton Foundation in 2005, which put Helmut Newton’s fashion images from the last two decades in the spotlight, the exhibition Helmut Newton: Fired took a look at his fashion photography from the 1960s and 1970s. Nearly 200 editorial images were on display.

“Fired from French Vogue: In 1964 I was commissioned by Queen magazine to photograph the revolutionary collection by Courrèges. The fashion editor, Claire Rendlesham, decided on a journalistic scoop showing only my Courrèges photos and excluding all other fashion houses from her Paris report. When Queen landed on the desk of Françoise de Langlade (then associate editor-in-chief of French Vogue) she hit the roof. I was called into her office, we had a tremendous row, she accused me of treachery and disloyalty and wanted to know why I had not told her about this scoop. I pointed out to her that I had no exclusive contract with Vogue, and it was of course understood that I would never divulge any ideas developed by French Vogue to Queen or vice versa. So I was kicked out of the hallowed halls of Vogue only to return in 1969 when Francine Crescent was appointed editor-in-chief. During Francine’s regime, I did what I considered my best fashion work. I was to be a regular contributor until 1982.”

Helmut Newton, from: Pages from the Glossies, Zurich: Scalo, 1998

Helmut Newton worked for numerous other international magazines in addition to Vogue and that he also worked directly with designers and fashion houses. The photographs for Courrèges that were published in 1964 in the fashion magazine Queen (and were the reason why Newton was fired from Vogue) brilliantly translated the ultra-modern designs of the French designer into the photographic image. The women’s trousers, the above-the-knee dresses and the spectacular space-age fashion in particular were revolutionary. The image of women and their position in society were in the midst of radical change. Newton shot the models without accessories in claustrophobic, narrow spaces, whose metal walls reflected and doubled both clothes and women.

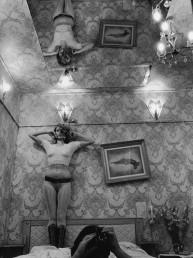

After Newton was fired from Vogue, Claude Brouet, who was Editor-in-Chief of Elle, offered him work at her magazine. Five years later, Newton also captured “Elle’s” models within the confines of a mirrored room; this time, however, the photographer himself appeared with his small-format camera behind the women. Dressed in black, his presence provided more than a mere tonal contrast to the light-colored Cardin and Lanvin clothing adorning the models. With a sense of self-irony and media reflexivity about his medium that was unusual for the times, Newton slipped himself behind the work process and into the fashion image, and on occasion even put his own camera into the hands of the models. Two years later in 1971, he developed the so-called “Newton Photo Machine,” a delayed-action release contraption, with which the female models systematically photographed themselves (and their clothes) in front of a mirror – thereby checking their own poses against their reflection. These photographs were also published in Elle, and in 2007 they could be seen at the Helmut Newton Foundation.

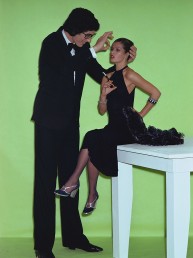

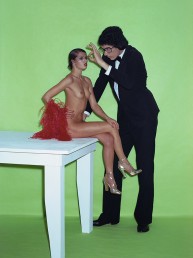

Helmut Newton staged fashion in the streets, in public spaces or, as he said, “in life,” more often than in the studio. He placed women on a metaphorical pedestal, which in contrast to earlier fashion photography, no longer consisted of gallantry, but rather of female self-confidence. Newton’s women posed seductively and aloof, standing on the engine hoods of American sedans, in front of huge Marlon Brando posters or mysteriously illuminated at dusk before lonesome buildings. His black and white prints remind us of scenes from Hitchcock films, while his color photographs could pass for precursors to the later movies of David Lynch. Newton portrays women as active and attractive, assertive and erotic creatures, who seem to dominate the scenery – as well as the men who appear in the occasional motif.

The studio atmospheres that we also encounter in many of the pictures have either the neutral, flat backgrounds of the classical studio cove or are complicated, theatrical architectures. Their character remains recognizable, as Newton always gives us a peek behind the scenes at the picture’s edge. Monochromatic backdrops keep to the bare minimum, while more pictorial settings playfully contextualize or interpret the fashion models. Newton rejected the excessive décor of earlier decades, even for his Chanel pictures; the settings always evoke a sense of visionary timeliness. Televisions are used in some of the fashion photos, creating an interesting interaction between the female model on the TV screen and the gawking male observer, thus conveying both the unattainability as well as the ephemerality of the mediated subject.

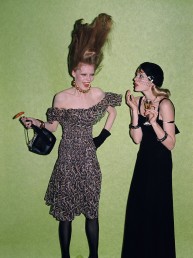

The women in Newton’s pictures appear separately or in a group, at times with alluring elegance, or playful anarchy. In the early 1970s, Newton shot a series for the magazine Nova with aggressive “naughty girls” throwing chairs hand grenades, or donned with smiling masks and holding diamond-studded knuckle busters into the camera. The images were disturbing and provocative – also a subtle comment on the demonstrations and street agitation in Europe’s cities at the time and the radicalization of bourgeois youth into terrorist rings. Newton’s fascination for strong women reached its zenith in the 1980s with the famous series of the larger-than-life Big Nudes. As the photographer explained once, the series was inspired by life-sized identity photos of RAF terrorists he had seen hanging in German police precincts.

Helmut Newton’s creative potential was already present in his fashion work of the 1960s, and as we know today, there was room to grow. The ingenious images he produced time and again did more than just portray fashion; they offered commentary and interpretation as well. This applies especially to his later commissions for Yves Saint Laurent and Blumarine.

Specific occasions and settings that Newton used as the backdrop for some of the photographs on display were social events like the World’s Fair in 1967 in Montreal, or allegedly private cocktail parties. It is seldom the everyday which has a place in his pictures; mostly it is heightened situations, particular moments, which Newton created especially for his images.

The editorial work that has been compiled for this newest exhibit has heretofore been published exclusively in magazines, showing fashion from Courrèges, Dior, Lanvin, Cardin, Yves Saint Laurent, Ricci, Roger Vivier, Marc de Carita, Mary Quant and others. The photographs filled the entire exhibition space of the Helmut Newton Foundation; beginning with the fashion photos of the revolutionary Courrèges designs of 1964 and ending a decade later with the wrestling women Newton photographed for Nova. Self-defense was seen as a radical and consequent form of female self-realization at the time. But Newton would not be Newton if he hadn’t taken staged the fights of his protagonists with an erotic twist them.

When he later returned to French Vogue with Francine Crescent at the reigns, one of the first editorials she printed by Newton in 1970 were his photos of the newest Courrèges line, coming full circle.

In recent years, fashion photography has liberated itself from magazines and become considered a leading medium in its own right. Numerous museum exhibits have followed this coup; the art and auction market has catapulted prints of not a few classical and contemporary fashion photographers into unforeseeable heights. That was still very different in the 1960s and 1970s, as Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, William Klein or Helmut Newton worked in magazine editorials. Some of their photographs have become iconic – and some of these icons may be seen in the exhibition: Helmut Newton: Fired.