With the exhibition Pigozzi and the Paparazzi in the Helmut Newton Foundation Paparazzi photography is the subject of an extensive show for the first time in Germany. The show concentrated on snapshots and portraits of famous people from the 1960’s and 1970’s, the “classic“ era of the paparazzi, and offers us a glimpse of how the mythic aura of the stars was dismantled by showing them going about their daily lives.

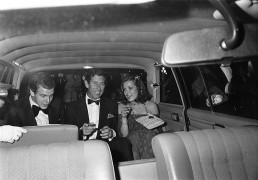

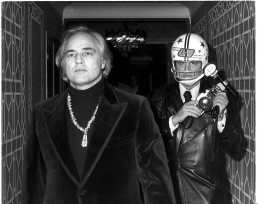

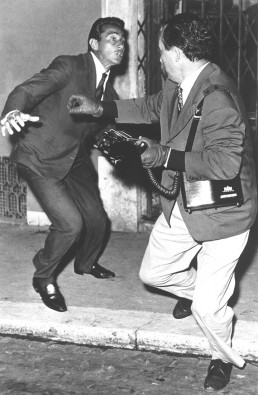

We encounter Alain Delon and Prince Charles, Mick Jagger and Woody Allen, Sophia Loren and Grace Kelly, Brigitte Bardot and Marlene Dietrich at parties, on the street, at the beach and so on. In hardly any of these photographs was there ever time for the subject to strike a pose. They were taken “from a safe distance” with the photographer often going unnoticed. Nevertheless, once in a while a fight would break out between the hunter and the hunted when a photographer got too close or was discovered in his hiding-place. For example, the photographer Ron Galella lost several teeth when he suffered a well-aimed punch from Marlon Brando; thereafter he often wore an American Football helmet any time he expected to come across Brando at a public event.

Presenting approximately 350 B/W and colour prints by Salomon, Weegee, Galella, Quinn, Angeli, Secchiaroli, Pigozzi and Newton, the exhibition displays the forerunners and central figures of Paparrazi Photography – and provides a visual commentary about the evolution of this phenomenon. The exhibition offers an overview and critical look at the history of a photographic genre dedicated to fame and sensationalism.

There will always be paparazzi shots that cross over into celebrity and portrait photography. Jean Pigozzi, the photographer included in the exhibition title, has been able to cultivate the kind of intensive and intimate relationship with the rich and the famous that is so desperately sought after by the paparazzi at large. He too penetrates into their private sphere, yet the celebrities generally acquiesce to the photographic unmasking with a smile.

Selected Works

Pigozzi and the Paparazzi

Matthias Harder

With the exhibition Pigozzi and the Paparazzi the “bad boys” of photography are the subject of an extensive show for the first time in Germany. Paparazzi photography is an aggressive form of photojournalism, particularly today when the famous names in show business are hunted down and pushed into dangerous situations for the sake of getting the most interesting picture possible. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, the “classic“ era of the paparazzi, the combination of voyeurism and exhibitionism, whereby photographers lie in wait for the stars to make their public appearance, was less strident and loud. Inventiveness, speed and persistence, along with a touch of cheekiness – put to use at the Cannes Film Festival, or on the Via Veneto in Rome – was usually enough to guarantee good results.

The exhibition Pigozzi and the Paparazzi concentrates on snapshots and portraits of famous people from this era and offers us a glimpse of how the mythic aura of the stars was dismantled by showing them going about their daily lives. We encounter Alain Delon and Prince Charles, Mick Jagger and Woody Allen, Sophia Loren and Grace Kelly, Brigitte Bardot and Gina Lollobrigida at parties, on the street, at the beach and so on. Most of these pictures were taken “from a safe distance” with the photographer going unnoticed. Nevertheless, once in a while a fight would break out between the hunter and the hunted when a photographer got too close or was discovered in his hiding-place. For example, the photographer Ron Galella lost several teeth when he suffered a well-aimed punch from Marlon Brando thereafter he often wore an American Football helmet any time he expected to come across Brando at a public event.

In hardly any of these photographs was there ever time for the subject to strike a pose. Most of the stars were caught by surprise, and to a certain extent many of these images were “stolen”. Contemporary paparazzi images are consciously excluded from the exhibition, since it is hard to discern any real photographic quality in the flood of images shot by “packs” of photographers, whose methods have become increasingly ruthless and their equipment mechanized. Today, more so than ever, magazines newspapers are highly interested in this kind of imagery. Regardless of quality and originality, it is sensation that counts.

The paparazzi were legendary, and today they are feared. In a way this all began in the 1930’s with Erich Salomon. A lawyer by training and a self-taught photographer, he gained access to major political events and was the first to secretly take photographs in a courtroom – something that was, and still is, forbidden. No one before him had dared risk doing this. Salomon used a camera with a very light-sensitive lens, which he usually hid in his briefcase or coat. Thus armed, he would find his way in to forbidden places, for example, the salons where high-ranking politicians of the era between the two World Wars pondered the new order of Europe. Occasionally he got caught, but he was hardly ever accused. One of his most famous pictures was taken when he photographed Aristide Briand, then the Foreign Minister of France, who called Salomon the “king of indiscretion,” the moment he discovered the photographer hiding behind a curtain in the Quai d’Orsay in Paris. A similar situation today is unimaginable.

Based in the USA, Arthur Fellig was a Polish-Hungarian photographer, who went by the name of Weegee and had a similarly unconventional style. He, however, focused on other subjects. By listening in on police radio Weegee would get a head start on police units and was often able to reach a scene early enough to photograph people who had suffered accidents, violence and other catastrophes. He was also drawn to those who did not get much from “the land of opportunity”; the homeless, the prostitutes and the drunks in the Bowery, and chronicled their lives with his camera.

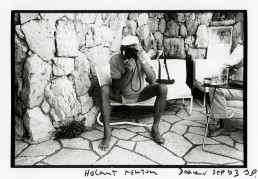

Helmut Newton appreciated the work of both Salomon and Weegee, both of whom could certainly be considered forerunners of the paparazzi. This is one of the reasons that the Helmut Newton Foundation (HNF) in Berlin was hosting this unique and comprehensive exhibition. Here, Newton’s works have already been presented in dialogue with a number of contemporaries whose work he appreciated, most recently in the exhibitions Men, War and Peace and Wanted.

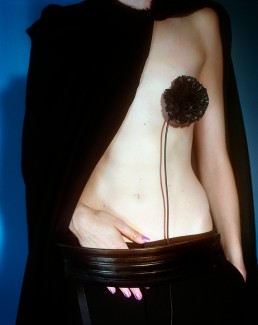

In his autobiography Newton wrote that after he saw Federico Fellini’s film La Dolce Vita starring Anita Ekberg, he became interested in the phenomenon of the paparazzi. In 1970 he travelled to Rome to work with “real” paparazzi. As part of a commission for the fashion magazine Linea Italiana, Newton hired a few of them to pose with his models. In Newton’s unconventional approach the photographers were asked to treat the model as if she were a famous person. An interesting aspect of Newton’s work is the combination of multiple real elements, such as the model, the fashion and the paparazzi, on the one hand, with the staging of the photograph on the other. In the 1980’s and 1990’s he aimed his camera at the paparazzi again – and they too aimed theirs at him – whilst he worked with his models on the Croisette, at the Cannes Film Festival.

The name of Fellini’s character Paparazzo from the film La Dolce Vita has since been adopted as the standard term for these kinds of photographers. The character was modeled after a real person: Tazio Secchiaroli, who later rose to become Fellini’s set photographer. In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s Secchiaroli and his colleagues waited nightly, with camera and flash in hand, for prominent victims on Rome’s Via Veneto. About the same time, Edward Quinn and Daniel Angeli were very active in the South of France, mainly on the Cote d’Azur, and often worked with very long lenses. The interactions between the photographers and their usually unwilling models is particularly exciting, especially when stars like Greta Garbo, or Marlene Dietrich, did their best to hide their faces. Working mostly in New York and Los Angeles, Ron Galella has long been a cult figure in the USA, and was both an influence upon and a mentor to many younger photographers.

Presenting approximately 350 B/W and colour prints by Salomon, Weegee, Galella, Quinn, Angeli, Secchiaroli, Pigozzi and Newton, the exhibition displays the forerunners and central figures of the “classic” period of Paparrazi photography – and provides a visual commentary about the evolution of this phenomenon. The exhibition offered an overview and critical look at the history of a photographic genre dedicated to fame and sensationalism. A genre that continues to feed the “Yellow Press” with exclusive reports on the comings and goings of the jet set in order to push the sales of their publications ever higher.

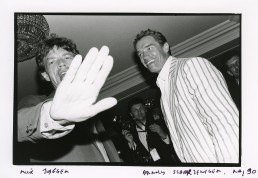

There will always be paparazzi photographs that cross over into celebrity and portrait photography. Jean Pigozzi, the photographer included in the exhibition title, has been able to cultivate the kind of intensive and intimate relationship with the rich and the famous that is so desperately sought after by the paparazzi at large. He too penetrates into their private sphere, yet the stars generally acquiesce to the photographic unmasking with a smile. Being befriended with many famous people in the international social and cultural scene, he has been making candid portraits of prominent individuals at private locations since the 1970’s. An unusual aspect of his work is his double portrait series Pigozzi & Co. In this ongoing project he appears together with a musician or an actor friend, the two posed with their heads, often touching, in a close-cropped composition. The photographer’s arm has been stretched outwards to aim the camera at himself and the person he is with. These are images from daily life, in which Pigozzi poses as friend and fan. In this manner he subtly takes the hunger for celebrity images to an absurd extreme and in doing so he ingeniously plays to this desire when he publishes the images in books, or exhibits them, as he does here at the HNF.

Now, at the beginning of the 21st century most paparazzi are no longer working in Rome, but in Los Angeles. It is there that Hollywood functions as the world’s largest production mechanism for the creation of images and illusions. While stars need, and sometimes like, to bathe in the flashing lights of the cameras during official events like film award ceremonies or charity parties, after the official appearance is over the camera shifts from its function as a promotional medium, into that of a weapon. It is a weapon gladly wielded by the eager hands and hungry eyes of the paparazzi. The photos captured during such “off-festival” encounters are occasionally deeply controversial, yet often very highly prized.